If you or anyone you know is interested in learning more or being a part of this, please contact me at: ggirl.kglr@gmail.com

Wednesday, November 27, 2019

New Project Ideas

I'm sort of brainstorming, but I'm thinking about starting some kind of podcast or platform for women to share their stories and talk about recovery, especially in running. Though I can't quite put my finger on it, I feel like something's missing. There needs to be more of a focus on action, recovery, and tangible acts to fix women's running. I have ideas about what this project could be, but I'm interested in networking with others.

Labels:

brainstorming,

magazine,

platform,

podcast,

shared blog

Saturday, November 23, 2019

Just How Broken Are Things?

Don't ever, ever, EVER, ever, EVER, ever, eeeeevvvveeerrrr, ever, ever EVER, ever go to Let's run if you want to avoid misogyny, hate, and comments that are even worse than those found on YouTube. Good god, that place is a cesspit of toxic waste. Online misogyny has increased in general over the last few years, but on Let's Run it's extraordinarily virulent.

When I recently saw one thread on Let’s Run about Mary Cain's allegations against her former coach, I was disgusted and felt physically sick. It's clear that the majority of individuals commenting are not exactly psychologically astute, but what's most disturbing isn't just seeing a complete lack of awareness of any given subject plastered all over a particular forum. The intentionally degrading and vicious comments are what's so shocking. Despite an obvious lack of knowledge about development, health, and quite a long list of other topics, it's surprising how vocal these arrogant individuals are when it comes to pretending to know what's best for other people, especially young women.

As I expected, people coming forward suggesting the solution to avoiding any kind of body image or eating issue is simply to resist being attached to a number on the scale opened the gate for others to misinterpret the bigger picture, which is that some women can have a positive experience and stay healthy throughout a running career. And heaven knows that's a message we all need right now. However, people look at what was meant to be a few words of hope and support (I think) and twisted it to make it seem like the real message is really that those who don't rise above it all are weak, which some of us expected, but not to this extent.There has always been an incorrect idea floating around that any addiction or mental illness can be overcome by will power. I’m just surprised how many people still believe this myth.

I've been saying it for a long time now, but these are not just women's problems. As much as some will point the finger at what they consider weak females, more than one in ten men suffer from depression in the United States, and male athletes are even more prone to depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts. In 2014, the American College Health Association found that, in their survey of about twenty thousand student-athletes, 21 percent of males reported feeling depressed, and 31 percent of them felt anxious. According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association, suicide is the third most common cause of death among student-athletes.

Some of the ugliest comments I saw on the running forum suggested a young girl is a wuss for crying or struggling, you know, being human. They insist Mary should have just lost the weight her coach wanted her to, despite the fact that she was already physically breaking down. Imagine what a lack of proper nutrition does to the brain and how that affects emotions. But even if there were no link to emotions and being properly rested and fed, why would anyone call a young girl weak for reacting to a shitty situation with frustration and tears? It seems quite normal to me. How else was her teenage self supposed to act?

I'm not going to fully address the negative comments Mary's teammate may have said. If it's true, whoever said it has to live with herself and her insensitive attitude. If true, it just shows how ill-equipped people are when it comes to handling someone else's pain and suffering.

My first year in college, I had a mini meltdown before a big workout when I felt frustrated that I couldn’t keep up with my teammates in our warm-up run. Fortunately, three of them stopped and comforted me. That’s all it took. My coach talked to me when we got to the track, and the support I received allowed me to put my frustration aside and get to work. That kind of compassion and understanding doesn’t happen in a toxic environment. Instead, the one struggling is left to internalize all her bad experiences, which only makes things worse.

The bottom line is that mental illness needs to be taken more seriously. We will never fix the problems related to abusive coaches in the running community if there's a refusal to take into consideration the mental health of athletes as well, and that applies to all sports. The two issues go hand in hand.

When I recently saw one thread on Let’s Run about Mary Cain's allegations against her former coach, I was disgusted and felt physically sick. It's clear that the majority of individuals commenting are not exactly psychologically astute, but what's most disturbing isn't just seeing a complete lack of awareness of any given subject plastered all over a particular forum. The intentionally degrading and vicious comments are what's so shocking. Despite an obvious lack of knowledge about development, health, and quite a long list of other topics, it's surprising how vocal these arrogant individuals are when it comes to pretending to know what's best for other people, especially young women.

As I expected, people coming forward suggesting the solution to avoiding any kind of body image or eating issue is simply to resist being attached to a number on the scale opened the gate for others to misinterpret the bigger picture, which is that some women can have a positive experience and stay healthy throughout a running career. And heaven knows that's a message we all need right now. However, people look at what was meant to be a few words of hope and support (I think) and twisted it to make it seem like the real message is really that those who don't rise above it all are weak, which some of us expected, but not to this extent.There has always been an incorrect idea floating around that any addiction or mental illness can be overcome by will power. I’m just surprised how many people still believe this myth.

I've been saying it for a long time now, but these are not just women's problems. As much as some will point the finger at what they consider weak females, more than one in ten men suffer from depression in the United States, and male athletes are even more prone to depression, anxiety, and suicidal thoughts. In 2014, the American College Health Association found that, in their survey of about twenty thousand student-athletes, 21 percent of males reported feeling depressed, and 31 percent of them felt anxious. According to the National Collegiate Athletic Association, suicide is the third most common cause of death among student-athletes.

Some of the ugliest comments I saw on the running forum suggested a young girl is a wuss for crying or struggling, you know, being human. They insist Mary should have just lost the weight her coach wanted her to, despite the fact that she was already physically breaking down. Imagine what a lack of proper nutrition does to the brain and how that affects emotions. But even if there were no link to emotions and being properly rested and fed, why would anyone call a young girl weak for reacting to a shitty situation with frustration and tears? It seems quite normal to me. How else was her teenage self supposed to act?

I'm not going to fully address the negative comments Mary's teammate may have said. If it's true, whoever said it has to live with herself and her insensitive attitude. If true, it just shows how ill-equipped people are when it comes to handling someone else's pain and suffering.

My first year in college, I had a mini meltdown before a big workout when I felt frustrated that I couldn’t keep up with my teammates in our warm-up run. Fortunately, three of them stopped and comforted me. That’s all it took. My coach talked to me when we got to the track, and the support I received allowed me to put my frustration aside and get to work. That kind of compassion and understanding doesn’t happen in a toxic environment. Instead, the one struggling is left to internalize all her bad experiences, which only makes things worse.

The bottom line is that mental illness needs to be taken more seriously. We will never fix the problems related to abusive coaches in the running community if there's a refusal to take into consideration the mental health of athletes as well, and that applies to all sports. The two issues go hand in hand.

Labels:

Athletics,

Mary Cain,

men,

mental illness,

running,

sports,

statistics,

suicide

Wednesday, November 20, 2019

Skimming The Surface

With so many individuals offering advice and expressing opinions about how to fix what's wrong with the running world, one thing is very, very clear to me. We need WAY more qualified people with a background in psychology stepping in here.

I'm not going to point fingers because I see most people mean well, but holy shitballs. If I see one more blog post, comment, or tweet suggesting the answer is simply that women should choose to be above it all, I might explode.

I have already gone over these issues on my blog, but to recap:

1. Eating disorders, body image problems, depression, and any other mental illness ARE NOT A CHOICE.

2. Mental illness is NOT any kind of weakness.

3. This is not just a women's issue.

4. Telling the world, "Well, that wasn't MY experience!" isn't all that helpful, unless you have some compassion for those struggling, a deeper understanding of of the underlying problems, and some legit advice about how things can be better.

5. Mary Cain was a child (as many of us were) when she was facing abuse by a coach, but psychological abuse happens to people of all ages.

6. This is NOT a debate about body composition, and that's a topic that should be addressed by the athlete and her team that hopefully includes a qualified coach, a licensed therapist, someone in the medical field, family, and/or anyone who truly wants her overall well-being to be a main focus. Weight or body composition is not a taboo topic, but some things are not your business.

7. The female triad is an incomplete measure of overall health and well-being or lack thereof. Many people struggle and don't lose a period, and this measure completely discounts men who have similar issues.

This might be one of my shortest blog posts, but I hope I'm making myself clear.

I'm not going to point fingers because I see most people mean well, but holy shitballs. If I see one more blog post, comment, or tweet suggesting the answer is simply that women should choose to be above it all, I might explode.

I have already gone over these issues on my blog, but to recap:

1. Eating disorders, body image problems, depression, and any other mental illness ARE NOT A CHOICE.

2. Mental illness is NOT any kind of weakness.

3. This is not just a women's issue.

4. Telling the world, "Well, that wasn't MY experience!" isn't all that helpful, unless you have some compassion for those struggling, a deeper understanding of of the underlying problems, and some legit advice about how things can be better.

5. Mary Cain was a child (as many of us were) when she was facing abuse by a coach, but psychological abuse happens to people of all ages.

6. This is NOT a debate about body composition, and that's a topic that should be addressed by the athlete and her team that hopefully includes a qualified coach, a licensed therapist, someone in the medical field, family, and/or anyone who truly wants her overall well-being to be a main focus. Weight or body composition is not a taboo topic, but some things are not your business.

7. The female triad is an incomplete measure of overall health and well-being or lack thereof. Many people struggle and don't lose a period, and this measure completely discounts men who have similar issues.

This might be one of my shortest blog posts, but I hope I'm making myself clear.

Monday, November 18, 2019

Why Is It So Hard

Most of us can sense when something is wrong, even if it's not something we can really put a finger on or explain to the fullest, some kind of moral dumbfounding. Then there are times when it's quite clear why something is wrong. To me, what I'm about to address is the latter, but oddly, at least one person doesn't think so.

I was about to take a break from blogging about the mess that is the running world right now, but then I stumbled upon the following tweet:

People addressed the issue from both sides, and that should have been enough. Points were made all around, and even though we didn't all agree, the air was cleared. Oh, but that's never enough. The original poster wanted to point out just how wrong anyone who took an opposing stance was. But the reason why some of us aren't laughing isn't because we're too dumb to get highbrow humor; it's because some shit just ain't funny.

Obviously, the tweet was meant as a joke. In the past, this person has made other "jokes" that reinforce diet culture and unhealthy relationships with food, especially around the holidays. It's the reason why I stopped paying much attention to him on social media a few years back, but this tweet made me take it one step further and unfollow him. I've mentioned others whom I have unfollowed for this same reason in previous blog posts. I admit, my tolerance for that kind of rhetoric is low. Their idea of funny is to use outdated ideas that suggest having to earn your food or beer or having to burn it off. In the eating disorder recovery community, these are the exact kinds of concepts that are triggering and outright dangerous to promote.

As much as "triggering" has become a bad word, it should be acknowledged because in certain communities, those who become triggered can resort to self-harm and even risk death. That aside, jokes about weight, overeating, and using food as a reward or punishment aren't funny. If you're aiming for comedy, at least try a new, more creative routine.

I considered not publishing this, but fuck it. I'm tired of people and their holier than thou attitudes disregarding people I care about in an effort to be funny or relevant.

My responses are in red. This blog post is what prompted me:

I was about to take a break from blogging about the mess that is the running world right now, but then I stumbled upon the following tweet:

People addressed the issue from both sides, and that should have been enough. Points were made all around, and even though we didn't all agree, the air was cleared. Oh, but that's never enough. The original poster wanted to point out just how wrong anyone who took an opposing stance was. But the reason why some of us aren't laughing isn't because we're too dumb to get highbrow humor; it's because some shit just ain't funny.

Obviously, the tweet was meant as a joke. In the past, this person has made other "jokes" that reinforce diet culture and unhealthy relationships with food, especially around the holidays. It's the reason why I stopped paying much attention to him on social media a few years back, but this tweet made me take it one step further and unfollow him. I've mentioned others whom I have unfollowed for this same reason in previous blog posts. I admit, my tolerance for that kind of rhetoric is low. Their idea of funny is to use outdated ideas that suggest having to earn your food or beer or having to burn it off. In the eating disorder recovery community, these are the exact kinds of concepts that are triggering and outright dangerous to promote.

As much as "triggering" has become a bad word, it should be acknowledged because in certain communities, those who become triggered can resort to self-harm and even risk death. That aside, jokes about weight, overeating, and using food as a reward or punishment aren't funny. If you're aiming for comedy, at least try a new, more creative routine.

I considered not publishing this, but fuck it. I'm tired of people and their holier than thou attitudes disregarding people I care about in an effort to be funny or relevant.

My responses are in red. This blog post is what prompted me:

When news broke recently about the fat shaming and related

psychological abuse that was suffered by members of the Nike Oregon

Project and by members of past British Olympic track and field teams at

the hands of their coaches, I, like so many others, found the alleged

behavior unconscionable. But I also found it absurd. It's unconscionable, yes, and if it weren't so widespread, it might also be absurd. The fact is, it happens a lot at all levels of the sport and is a very real and very painful experience for those who are being shamed. Worse, some individuals, no matter their weight, begin to believe the abuser's words.

Let’s be clear: Fat shaming any athlete (or nonathlete, for that matter) is unconscionable. But fat shaming an elite athlete whose body is finely tuned to perform at the very highest level is both unconscionable and kind of ridiculous. But it happens, and these kinds of problems are happening now, in real time, to many athletes and non-athletes.

I’ve always had an absurdist sense of humor. So, it wasn’t long after I read these disturbing reports that I found myself imagining the absurd scenario of a thickheaded coach trying to distance himself from the likes of Alberto Salazar and Charles van Commenee by announcing that he only fat-shamed athletes who actually were fat. It amused me to picture a coach so utterly clueless about what is actually wrong about fat shaming that he believed his behavior (fat shaming only truly fat athletes) was materially different from the behavior described in the reports (fat shaming finely tuned elite athletes). OK, we get he likes the word absurd, but, again, this wasn't an isolated incidence. These kinds of problems have been occurring for years at all levels in the sport, in other sports, and in general. It isn't just one or two coaches, and the actual weight of the athlete or size isn't the problem. Psychological and emotional abuse is the deeper issue. This happens to athletes of all sizes. Fat is used by abusive individuals in these cases as a general insult like any other, specifically to put down and humiliate a person or to attempt to gain control over her by emotionally abusing her. Getting into why using fat as an insult is wrong is a whole other can of worms I'm sidestepping for now, but it's a related topic.

Now, it so happens that I myself am an endurance coach and writer who has written extensively on the topic of performance weight management. In consideration of this fact, I got it into my head to post a tweet in the character of a thickheaded coach who thought the crime that the accused coaches committed was not fat shaming per se but fat-shaming athletes who weren’t fat. So I did, and let’s just say that the joke was not well received. Clearly, and it's not the fault of the audience. Women and men of all sizes and shapes experience fat shaming. I find little humor in the idea that a coach did an oopsie and fat shamed the wrong body type.

As the pile-on continued (it was hardly a pile-on, more of a debate with some in support of bad humor and others not), I thought about what went wrong, and I came to the conclusion that my chief mistake was to assume that my Twitter followers had sufficient context to appreciate the joke as it was intended. (He didn't think hard enough) On further reflection, I decided the same joke probably would have gotten a few more laughs and a little less criticism if it were delivered as a set piece in a television show or film, where a good comedic actor delivered the very same words I used in my tweet in a manner that invited viewers to laugh at his thick-headedness. (I doubt that very much.) But that’s neither here nor there, because I am not a screenwriter, I’m an endurance coach with a Twitter account. I'm 100 percent sure I'm not the only one cringing at this.

I don’t think the context issue was the only factor involved in the joke’s flat landing, however. Rather, I think the negativity directed at me has been fueled in part by an ongoing backlash against our focus on body weight in endurance sports. As the author of the book Racing Weight, I am keenly aware that a growing contingent within the endurance community believes that, misfired jokes notwithstanding, the topic of performance weight management ought to be more or less taboo. Long before I posted my tweet, it was suggested to me, more than once, that I did something wrong in writing Racing Weight. I never saw it until after the "joke" nosedived, but OK. I think most people who said anything have more of a problem with the title, not the content.

The specific accusation is that in discussing weight management as a tool for performance, folks like me contribute to an unhealthy fixation on weight in endurance sports that motivates some coaches to fat-shame and psychologically abuse athletes and causes some athletes to develop issues such as eating disorders and body dysmorphia even without a coach’s overt influence. The solution, therefore, is to avoid discussing performance weight management except for the sake of actively discourage athletes from focusing on it. That wasn't the specific accusation. Again, the issue isn't weight so much as the abuse. There are all kinds of resources available that help athletes eat and train optimally. There are ways to discuss these kinds of concerns without joking, belittling, or triggering others. Rachael Steil offers some great resources on her blog.

The intent here is unimpeachable. Eating disorders, body dysmorphia, and over-fixation on body weight are huge problems in endurance sports, and anyone in a position to do something to fix them has an obligation to chip in. As one who is very much in such a position, I try hard to do my part. (Apparently not hard enough) I think the Twitter critics who read my tweet literally (Nope, missed the point again) —who actually think I fat-shame some athletes (eye roll)—would be surprised to see how I counsel the athletes I coach on these matters. I never encourage athletes to lose weight, I preach caution to all of those who set their own goal to lose weight, and I talk to them a lot more about the importance of having a healthy relationship with food than I do about the mechanics of shedding body fat. I’m proud to say I’ve brought a few athletes back from very dark places through these means. I don't think the majority of people arguing were suggesting he actually fat shames anyone, more that this kind of post is inconsiderate, especially considering the current climate in the running world. A good comedian not only reads the room but doesn't need several paragraphs to explain the "joke". And do some research. Fat shaming doesn't just hurt the one being shamed. It hurts those who watch it. This "joke" is one step removed. In other words, this tweet that he's so desperately trying to defend is potentially hurting others merely by suggestion.

And that doesn't mean anyone is taking it literally. It's the idea of it, the suggestion that gets in a person's head. It is offensive. That might be hard for people to understand, but one doesn't have to take a statement like that literally to be affected by it. And because it has been the norm for so long for "fat" to be the brunt of jokes, we often don't recognize how damaging it can be to make offhanded comments like that. In his head, it was funny and absurd, but to write it that way out of context shows insensitivity.

Having said all of this, I must also say that I disagree with those who believe that the topic of performance weight management ought to be taboo, for two reasons. The first is that, in my experience, forbidding an open, rational discussion of the topic only drives athletes’ efforts to manage their weight underground, which greatly increases the likelihood that they’ll go about it the wrong way. It’s sort of like the argument that is often made for teaching sexual education in school. Folks are going to do it regardless of whether you tell them not to, so why not talk openly about how to do it and how not to do it? Um, who said it's taboo? Obviously, there are sensible ways to address weight that don't include body shaming, using terms that could be considered offensive, or ridiculing. The condescending way in which this guy addresses his audience is amusing considering the backlash he received. That takes some balls.

The second reason I deem the racing weight backlash misguided is that, as a general principle, I believe that truth is the only road to effective solutions for all problems. I think we do athletes a disservice when we assume they can’t handle the truth. A small minority of athletes, those who have a history of disordered eating or who are at high risk for developing an eating disorder, do need to be steered away from giving any mind space to their weight and body shape. (he just said it's a huge problem in endurance sports, but now only a few people are at risk?)I half-jokingly tell the athletes I coach who belong to this minority, “My one and only prescription for you is to spend 80 percent less time thinking about food.” But I think it’s a mistake to establish general rules for the discussion of performance weight management based on the vulnerabilities of this small group. No, all kinds of nope here. It is most definitely not a small minority who have a history of eating disorders or are at risk. Even as far back as 2004, studies showed that athletes are up to three times more likely to develop an eating disorder. I may have cited this before, but here are some statistics on athletes and eating disorders. And apparently this guy is magic and can see beforehand which athlete is susceptible to developing an eating disorder and which isn't. Pretty impressive... if it were only true.

Again, good coaches look at how to train different body types differently. What's absurd is thinking several paragraphs of blah blah counters a tweet that offended many people for good reason. Instead of a simple apology or taking it down or just leaving it be after people offered opinions, he wrote this? I mean, really. Stop putting the blame on those who have lived it and are upset by this kind of poorly thought out comment.

Instead, in my view, the “standard” approach to dealing with performance weight management should be based on facts and truth. And here are the most relevant truths, as I see them:

1. Body weight and body composition can affect endurance performance both positively and negatively. Again, I don't think anyone was arguing otherwise.

2. There is nothing intrinsically wrong or dangerous about actively managing one’s weight and body composition in the pursuit of better performance. Jesus. Talk about missing the point. No, there's not, unless a coach bullies an athlete to the point where she self harms. And that's what the topic of conversation has been lately.

3. There are safe, healthy, and effective ways to pursue one’s optimal racing weight and there are unsafe, unhealthy, and ineffective ways. Nobody said otherwise.

4. The desire to actively pursue optimal racing weight should come from the individual athlete and should never come from a coach or anyone else. Racing weight shouldn't be the goal. Performance and health should be.

5. Athletes who express such a desire should receive (ideally professional) guidance that is evidence-based and that is informed every bit as much by psychological concerns as by physical ones. For example, it should be drilled into athletes’ heads that optimal racing weight is determined functionally (i.e., by how the athlete feels and performs), not by the scale, and least of all by arbitrary numerical goals. Agree, but then one has to question why even call it race weight?

6. Athletes who have expressed a goal to actively pursue their racing weight (well, I hope nobody does, because after just explaining how athletes should focus on performance, we are back focusing on weight as a goal.) and who start heading in a bad direction (And how does one know when they start?), either physically or psychologically, despite qualified guidance, should be supported in letting go of weight management as a performance tool and encouraged to focus instead on some of the many other available tools. . .

. . . like performance-enhancing drugs! <----- Well, at least that was funny.

Ah, Lord help me.

Let’s be clear: Fat shaming any athlete (or nonathlete, for that matter) is unconscionable. But fat shaming an elite athlete whose body is finely tuned to perform at the very highest level is both unconscionable and kind of ridiculous. But it happens, and these kinds of problems are happening now, in real time, to many athletes and non-athletes.

I’ve always had an absurdist sense of humor. So, it wasn’t long after I read these disturbing reports that I found myself imagining the absurd scenario of a thickheaded coach trying to distance himself from the likes of Alberto Salazar and Charles van Commenee by announcing that he only fat-shamed athletes who actually were fat. It amused me to picture a coach so utterly clueless about what is actually wrong about fat shaming that he believed his behavior (fat shaming only truly fat athletes) was materially different from the behavior described in the reports (fat shaming finely tuned elite athletes). OK, we get he likes the word absurd, but, again, this wasn't an isolated incidence. These kinds of problems have been occurring for years at all levels in the sport, in other sports, and in general. It isn't just one or two coaches, and the actual weight of the athlete or size isn't the problem. Psychological and emotional abuse is the deeper issue. This happens to athletes of all sizes. Fat is used by abusive individuals in these cases as a general insult like any other, specifically to put down and humiliate a person or to attempt to gain control over her by emotionally abusing her. Getting into why using fat as an insult is wrong is a whole other can of worms I'm sidestepping for now, but it's a related topic.

Now, it so happens that I myself am an endurance coach and writer who has written extensively on the topic of performance weight management. In consideration of this fact, I got it into my head to post a tweet in the character of a thickheaded coach who thought the crime that the accused coaches committed was not fat shaming per se but fat-shaming athletes who weren’t fat. So I did, and let’s just say that the joke was not well received. Clearly, and it's not the fault of the audience. Women and men of all sizes and shapes experience fat shaming. I find little humor in the idea that a coach did an oopsie and fat shamed the wrong body type.

As the pile-on continued (it was hardly a pile-on, more of a debate with some in support of bad humor and others not), I thought about what went wrong, and I came to the conclusion that my chief mistake was to assume that my Twitter followers had sufficient context to appreciate the joke as it was intended. (He didn't think hard enough) On further reflection, I decided the same joke probably would have gotten a few more laughs and a little less criticism if it were delivered as a set piece in a television show or film, where a good comedic actor delivered the very same words I used in my tweet in a manner that invited viewers to laugh at his thick-headedness. (I doubt that very much.) But that’s neither here nor there, because I am not a screenwriter, I’m an endurance coach with a Twitter account. I'm 100 percent sure I'm not the only one cringing at this.

I don’t think the context issue was the only factor involved in the joke’s flat landing, however. Rather, I think the negativity directed at me has been fueled in part by an ongoing backlash against our focus on body weight in endurance sports. As the author of the book Racing Weight, I am keenly aware that a growing contingent within the endurance community believes that, misfired jokes notwithstanding, the topic of performance weight management ought to be more or less taboo. Long before I posted my tweet, it was suggested to me, more than once, that I did something wrong in writing Racing Weight. I never saw it until after the "joke" nosedived, but OK. I think most people who said anything have more of a problem with the title, not the content.

The specific accusation is that in discussing weight management as a tool for performance, folks like me contribute to an unhealthy fixation on weight in endurance sports that motivates some coaches to fat-shame and psychologically abuse athletes and causes some athletes to develop issues such as eating disorders and body dysmorphia even without a coach’s overt influence. The solution, therefore, is to avoid discussing performance weight management except for the sake of actively discourage athletes from focusing on it. That wasn't the specific accusation. Again, the issue isn't weight so much as the abuse. There are all kinds of resources available that help athletes eat and train optimally. There are ways to discuss these kinds of concerns without joking, belittling, or triggering others. Rachael Steil offers some great resources on her blog.

The intent here is unimpeachable. Eating disorders, body dysmorphia, and over-fixation on body weight are huge problems in endurance sports, and anyone in a position to do something to fix them has an obligation to chip in. As one who is very much in such a position, I try hard to do my part. (Apparently not hard enough) I think the Twitter critics who read my tweet literally (Nope, missed the point again) —who actually think I fat-shame some athletes (eye roll)—would be surprised to see how I counsel the athletes I coach on these matters. I never encourage athletes to lose weight, I preach caution to all of those who set their own goal to lose weight, and I talk to them a lot more about the importance of having a healthy relationship with food than I do about the mechanics of shedding body fat. I’m proud to say I’ve brought a few athletes back from very dark places through these means. I don't think the majority of people arguing were suggesting he actually fat shames anyone, more that this kind of post is inconsiderate, especially considering the current climate in the running world. A good comedian not only reads the room but doesn't need several paragraphs to explain the "joke". And do some research. Fat shaming doesn't just hurt the one being shamed. It hurts those who watch it. This "joke" is one step removed. In other words, this tweet that he's so desperately trying to defend is potentially hurting others merely by suggestion.

And that doesn't mean anyone is taking it literally. It's the idea of it, the suggestion that gets in a person's head. It is offensive. That might be hard for people to understand, but one doesn't have to take a statement like that literally to be affected by it. And because it has been the norm for so long for "fat" to be the brunt of jokes, we often don't recognize how damaging it can be to make offhanded comments like that. In his head, it was funny and absurd, but to write it that way out of context shows insensitivity.

Having said all of this, I must also say that I disagree with those who believe that the topic of performance weight management ought to be taboo, for two reasons. The first is that, in my experience, forbidding an open, rational discussion of the topic only drives athletes’ efforts to manage their weight underground, which greatly increases the likelihood that they’ll go about it the wrong way. It’s sort of like the argument that is often made for teaching sexual education in school. Folks are going to do it regardless of whether you tell them not to, so why not talk openly about how to do it and how not to do it? Um, who said it's taboo? Obviously, there are sensible ways to address weight that don't include body shaming, using terms that could be considered offensive, or ridiculing. The condescending way in which this guy addresses his audience is amusing considering the backlash he received. That takes some balls.

The second reason I deem the racing weight backlash misguided is that, as a general principle, I believe that truth is the only road to effective solutions for all problems. I think we do athletes a disservice when we assume they can’t handle the truth. A small minority of athletes, those who have a history of disordered eating or who are at high risk for developing an eating disorder, do need to be steered away from giving any mind space to their weight and body shape. (he just said it's a huge problem in endurance sports, but now only a few people are at risk?)I half-jokingly tell the athletes I coach who belong to this minority, “My one and only prescription for you is to spend 80 percent less time thinking about food.” But I think it’s a mistake to establish general rules for the discussion of performance weight management based on the vulnerabilities of this small group. No, all kinds of nope here. It is most definitely not a small minority who have a history of eating disorders or are at risk. Even as far back as 2004, studies showed that athletes are up to three times more likely to develop an eating disorder. I may have cited this before, but here are some statistics on athletes and eating disorders. And apparently this guy is magic and can see beforehand which athlete is susceptible to developing an eating disorder and which isn't. Pretty impressive... if it were only true.

Again, good coaches look at how to train different body types differently. What's absurd is thinking several paragraphs of blah blah counters a tweet that offended many people for good reason. Instead of a simple apology or taking it down or just leaving it be after people offered opinions, he wrote this? I mean, really. Stop putting the blame on those who have lived it and are upset by this kind of poorly thought out comment.

Instead, in my view, the “standard” approach to dealing with performance weight management should be based on facts and truth. And here are the most relevant truths, as I see them:

1. Body weight and body composition can affect endurance performance both positively and negatively. Again, I don't think anyone was arguing otherwise.

2. There is nothing intrinsically wrong or dangerous about actively managing one’s weight and body composition in the pursuit of better performance. Jesus. Talk about missing the point. No, there's not, unless a coach bullies an athlete to the point where she self harms. And that's what the topic of conversation has been lately.

3. There are safe, healthy, and effective ways to pursue one’s optimal racing weight and there are unsafe, unhealthy, and ineffective ways. Nobody said otherwise.

4. The desire to actively pursue optimal racing weight should come from the individual athlete and should never come from a coach or anyone else. Racing weight shouldn't be the goal. Performance and health should be.

5. Athletes who express such a desire should receive (ideally professional) guidance that is evidence-based and that is informed every bit as much by psychological concerns as by physical ones. For example, it should be drilled into athletes’ heads that optimal racing weight is determined functionally (i.e., by how the athlete feels and performs), not by the scale, and least of all by arbitrary numerical goals. Agree, but then one has to question why even call it race weight?

6. Athletes who have expressed a goal to actively pursue their racing weight (well, I hope nobody does, because after just explaining how athletes should focus on performance, we are back focusing on weight as a goal.) and who start heading in a bad direction (And how does one know when they start?), either physically or psychologically, despite qualified guidance, should be supported in letting go of weight management as a performance tool and encouraged to focus instead on some of the many other available tools. . .

. . . like performance-enhancing drugs! <----- Well, at least that was funny.

Ah, Lord help me.

Thursday, November 14, 2019

While I'm at It

As more and more women in the athletic community come forward with stories of harassment and abuse at the hands of coaches and trainers, there are some comments about weight and female runners that show not everyone understands the issues. One gentleman on Twitter suggested the East African runners must be laughing at us, but I doubt that. I had a former coach, one I admire and trust, who let me in on a little secret that eating disorders and coaching abuses are more widespread than people think. Look at the scandal that took place in Uganda when female athletes accused male coaches of sexual abuse years ago. It's ridiculous to think that women from other countries would be immune to the same pressures and negative comments, just like they're not immune to the pressures of doping, as we have seen.

In many instances, the conversation keeps turning to looks or weight, specifically the appropriate racing weight of female athletes, but this movement is about uncovering abuses of power. Besides, there are healthy ways to discuss weight that don’t include calling someone fat, obsessing about a number on the scale, or judging a body on appearance.

Seeing other people come forward and share their stories after Mary Cain opened up about her experiences running with Alberto Salazar and then leaving the program has naturally stirred up some memories of my own.

Something Mary said really resonated with me when she talked about the times she considered going back to her coach. She Tweeted, "I wanted closure, wanted an apology for never helping me when I was cutting, and in my own, sad, never-fully healed heart, wanted Alberto to still take me back. I still loved him. Because when we let people emotionally break us, we crave more than anything their very approval."

Wanting approval from those who can't or won't offer it has been a theme in my life since I can remember, but it was especially true regarding those who offered intermittent attention, including my high school coach. I know I'm not alone when I say the athlete-coach relationship is a complicated one. This applies to many areas of life. Damn, we all just want to fit in and be heard and acknowledged and feel some love now and then. Life is fucking hard. It helps to have support.

There's no doubt that I walked into adulthood loaded with baggage, damaged, broken, and emotionally scarred. This led to severe depression. It was, in addition to genetics and brain chemistry, directly related to the chaos I faced in my childhood. Regarding the abusers from my childhood, there was never any closure. I had to smile and pretend the abuse never happened. I certainly never got an apology for the actions of bullies and those who took advantage of me, and that left me vulnerable to repeating the cycle as I got older.

When I look at my high school coach, I carried around a lot of anger and resentment years after graduating and leaving his program, but I did go back for a summer of training and racing in college. And I got more hurt in the end and was called a head case. It's only more recently that I have let all of that go. In my book, I see how guarded I was writing about my experiences, taking a lot of the blame, but there were things he said that I can never forget. And yet, people are rarely all bad. In his case, he did a lot for me. In many ways, he helped me achieve some of my loftiest goals in life, but it was often at the expense of my mental and physical health. It wasn't entirely his fault, but he did a lot of damage. And I'm not alone in that, either. Several other runners on my team suffered, and it wasn't just the women who did.

I mentioned previously that some of the people who once denied the prevalence of eating disorders at the professional level are now encouraging women to come forward and tell their stories or retell them. While I see we are pretty much on the same side and basically want the same changes, I wouldn't really want to share my story again in the presence (virtual or otherwise) of someone who basically shot me down. It's not that this one person in particular was outright mean to me, more that her tone was condescending, accusatory, even. People who take a haughty stance have never impressed me, but in certain situations, they can be intimidating. Unfortunately, I didn't address it at the time. See a pattern here?

It wasn't until later that I realized how much this interaction affected me. I was caught off guard in the moment and had trouble rebounding after sharing what I went through led to an entire discussion about how those with eating disorders couldn't last at the professional level and how you just don't see it blah blah something about statistics being exaggerated, which is not true, but, again, it threw me to the point where I didn't know how to respond. This may seem trivial, but I felt very much like I was being discounted and put down in a way, like you have to be strong and above it all to compete as a pro, something I clearly failed at accomplishing, even though I was at a pro level for a while, just not able to accept money for my efforts. Anyway, because I didn't stand up and call bullshit at the time, it left me taking indirect swipes at this person years later, something I'm not real proud of. At the same time, I just don't want to engage with her, at all.

That happens a lot with individuals who have been bullied. An upsetting incident happens, and we go numb at the time, only to have a reaction later on, some kind of delayed stress response. So while I will share these kinds of thoughts here, I have no desire to confront the person who did this, privately or publicly. On social media, you're not only in a conversation with one person. Their followers are sure to jump in, and that can get ugly, at least from what I've seen. In the end, I'm glad there are people speaking out and supporting those who come forward.

My own resentment and story aside, what's unreal to me is that, despite the tremendous support those who were abused are receiving, some people are still defending a rotten coach.

A good coach doesn't fat or body shame his (or her) athletes.

A good coach finds the appropriate training program for each athlete, and that will vary based on a lot of things, including body type. The solution to an athlete's success isn't "lose more weight," it's "how can we get you to train and run optimally given where you are right now?"

A good coach creates and environment of camaraderie and support and doesn't pit one athlete against another.

A good coach trains different body types differently, in case that wasn't clear.

A good coach communicates well with his athletes and anyone involved in her (or his) training.

A good coach supports his athlete and encourages her to use outside support in the form of dietitians, therapists, strength coaches, and physical therapists.

A good coach doesn't encourage cheating.

A good coach looks at what can be changed in order to see improvements instead of placing all the blame on the athlete.

Lastly, someone pointed me to this rubbish, a calculator that, according the the RunBundle website, helps you find your ideal racing weight, but then adds: "Finally, although the majority of elite athletes we've tested do fit - or come close to fitting - the suggested weight ranges, there are anomalies. So, even if you're aiming for the podium, don't let an awkward Stillman result upset you." Too fucking late, assholes. Too fucking late. This is a dangerous and unhelpful "tool" and suggests nothing, a big fat zero about health and running capability. It doesn't take into consideration age, build, overall strength, flexibility, and, of course, mental health. It actually calculated my racing weight as a number that I was when I was anorexic, about the sickest I have been while still running. So fuck this bullshit, and fuck this company for putting out a potentially damaging gadget.

In many instances, the conversation keeps turning to looks or weight, specifically the appropriate racing weight of female athletes, but this movement is about uncovering abuses of power. Besides, there are healthy ways to discuss weight that don’t include calling someone fat, obsessing about a number on the scale, or judging a body on appearance.

Seeing other people come forward and share their stories after Mary Cain opened up about her experiences running with Alberto Salazar and then leaving the program has naturally stirred up some memories of my own.

Something Mary said really resonated with me when she talked about the times she considered going back to her coach. She Tweeted, "I wanted closure, wanted an apology for never helping me when I was cutting, and in my own, sad, never-fully healed heart, wanted Alberto to still take me back. I still loved him. Because when we let people emotionally break us, we crave more than anything their very approval."

Wanting approval from those who can't or won't offer it has been a theme in my life since I can remember, but it was especially true regarding those who offered intermittent attention, including my high school coach. I know I'm not alone when I say the athlete-coach relationship is a complicated one. This applies to many areas of life. Damn, we all just want to fit in and be heard and acknowledged and feel some love now and then. Life is fucking hard. It helps to have support.

There's no doubt that I walked into adulthood loaded with baggage, damaged, broken, and emotionally scarred. This led to severe depression. It was, in addition to genetics and brain chemistry, directly related to the chaos I faced in my childhood. Regarding the abusers from my childhood, there was never any closure. I had to smile and pretend the abuse never happened. I certainly never got an apology for the actions of bullies and those who took advantage of me, and that left me vulnerable to repeating the cycle as I got older.

When I look at my high school coach, I carried around a lot of anger and resentment years after graduating and leaving his program, but I did go back for a summer of training and racing in college. And I got more hurt in the end and was called a head case. It's only more recently that I have let all of that go. In my book, I see how guarded I was writing about my experiences, taking a lot of the blame, but there were things he said that I can never forget. And yet, people are rarely all bad. In his case, he did a lot for me. In many ways, he helped me achieve some of my loftiest goals in life, but it was often at the expense of my mental and physical health. It wasn't entirely his fault, but he did a lot of damage. And I'm not alone in that, either. Several other runners on my team suffered, and it wasn't just the women who did.

I mentioned previously that some of the people who once denied the prevalence of eating disorders at the professional level are now encouraging women to come forward and tell their stories or retell them. While I see we are pretty much on the same side and basically want the same changes, I wouldn't really want to share my story again in the presence (virtual or otherwise) of someone who basically shot me down. It's not that this one person in particular was outright mean to me, more that her tone was condescending, accusatory, even. People who take a haughty stance have never impressed me, but in certain situations, they can be intimidating. Unfortunately, I didn't address it at the time. See a pattern here?

It wasn't until later that I realized how much this interaction affected me. I was caught off guard in the moment and had trouble rebounding after sharing what I went through led to an entire discussion about how those with eating disorders couldn't last at the professional level and how you just don't see it blah blah something about statistics being exaggerated, which is not true, but, again, it threw me to the point where I didn't know how to respond. This may seem trivial, but I felt very much like I was being discounted and put down in a way, like you have to be strong and above it all to compete as a pro, something I clearly failed at accomplishing, even though I was at a pro level for a while, just not able to accept money for my efforts. Anyway, because I didn't stand up and call bullshit at the time, it left me taking indirect swipes at this person years later, something I'm not real proud of. At the same time, I just don't want to engage with her, at all.

That happens a lot with individuals who have been bullied. An upsetting incident happens, and we go numb at the time, only to have a reaction later on, some kind of delayed stress response. So while I will share these kinds of thoughts here, I have no desire to confront the person who did this, privately or publicly. On social media, you're not only in a conversation with one person. Their followers are sure to jump in, and that can get ugly, at least from what I've seen. In the end, I'm glad there are people speaking out and supporting those who come forward.

My own resentment and story aside, what's unreal to me is that, despite the tremendous support those who were abused are receiving, some people are still defending a rotten coach.

A good coach doesn't fat or body shame his (or her) athletes.

A good coach finds the appropriate training program for each athlete, and that will vary based on a lot of things, including body type. The solution to an athlete's success isn't "lose more weight," it's "how can we get you to train and run optimally given where you are right now?"

A good coach creates and environment of camaraderie and support and doesn't pit one athlete against another.

A good coach trains different body types differently, in case that wasn't clear.

A good coach communicates well with his athletes and anyone involved in her (or his) training.

A good coach supports his athlete and encourages her to use outside support in the form of dietitians, therapists, strength coaches, and physical therapists.

A good coach doesn't encourage cheating.

A good coach looks at what can be changed in order to see improvements instead of placing all the blame on the athlete.

Lastly, someone pointed me to this rubbish, a calculator that, according the the RunBundle website, helps you find your ideal racing weight, but then adds: "Finally, although the majority of elite athletes we've tested do fit - or come close to fitting - the suggested weight ranges, there are anomalies. So, even if you're aiming for the podium, don't let an awkward Stillman result upset you." Too fucking late, assholes. Too fucking late. This is a dangerous and unhelpful "tool" and suggests nothing, a big fat zero about health and running capability. It doesn't take into consideration age, build, overall strength, flexibility, and, of course, mental health. It actually calculated my racing weight as a number that I was when I was anorexic, about the sickest I have been while still running. So fuck this bullshit, and fuck this company for putting out a potentially damaging gadget.

Labels:

coaching,

eating disorders,

Mary Cain,

resentment,

running,

Salazar,

weight

Wednesday, November 13, 2019

I'll Make This Quick

Last night, I watched a "reporter", Ken Goe, who wrote a very one-sided, ass-kissing "article" on Salazar's response to Mary Cain's accusations against her former coach, get into a Twitter spat with Kara Goucher, who handled the situation with a lot more sophistication than her sparring partner. He suggested she was copping out and not stepping up because she didn't contact him to be interviewed, but Surprise! Potential interviewees aren't supposed to be the one to contact reporters for the work the reporter is doing. That's his job, not Kara's, and she has been very vocal about being willing to talk to people.

Twitter drama aside, people are calling this guy out for producing a piece of journalism that's biased, but there are more disturbing details in what he wrote, some subtle and some more blatant. What's clear is that this guy didn't take the time to do any real reporting; he just concocted a fluff piece basically claiming Salazar is good, now, for all my fellow Crime in Sports followers. However, Salazar's period of grace is long gone, and is trajectory is going to continue spiraling down, I believe.

Right from the start, Ken gets it wrong. Really, the first sentence is garbage:

Under fire from women runners for his training methodology, former Nike Oregon Project coach Alberto Salazar issued a statement Tuesday to explain his actions and apologize.

1. It's not just women runners (female runners) who are upset. Men are just as concerned, and plenty of people outside of the running community are, too, including Kamala Harris, who made a statement on Twitter in support of Cain.

2. Salazar never actually successfully explained his actions or apologized.

What Salazar does instead of apologizing is a classic narcissistic move. He states, "If I was callous or insensitive, I apologize," which puts the burden on the victim. "I'm sorry you felt that way" is quite different from "I'm sorry I hurt you." What many of us feel like he should have said is, "I'm sorry I failed you as a coach and created a toxic environment that encouraged the decline of your mental and physical health to the point where you were self-harming and unable to run to your potential," but that would probably be too much to ask.

Though Ken mentions three former NOP athletes who have also come forward to corroborate what Mary is saying, his article has only one brief quote by one of them, a single sentence. The rest of the piece is several paragraphs of back and forth, one long quote by Salazar, one paragraph defending him. And repeat.

The biggest issue I have with this kind of writing is that it discounts the victim. Instead of using her words, Ken downplays her experience by suggesting her career trailed off due to injury. No, it didn't. It trailed off because she was struggling and her coach and those around her didn't or weren't able to come to her aid. This was not her fault. Ken also didn't include the voice of other athletes who witnessed the way Salazar treated his athletes and have come forward.

The bottom line is that this is trash reporting. I could go on and on, but there's no real need. I think people see what kind of bullshit this is, and while the author eventually apologized to Kara for being an asshole on Twitter, he has a lot more to apologize for.

Twitter drama aside, people are calling this guy out for producing a piece of journalism that's biased, but there are more disturbing details in what he wrote, some subtle and some more blatant. What's clear is that this guy didn't take the time to do any real reporting; he just concocted a fluff piece basically claiming Salazar is good, now, for all my fellow Crime in Sports followers. However, Salazar's period of grace is long gone, and is trajectory is going to continue spiraling down, I believe.

Right from the start, Ken gets it wrong. Really, the first sentence is garbage:

Under fire from women runners for his training methodology, former Nike Oregon Project coach Alberto Salazar issued a statement Tuesday to explain his actions and apologize.

1. It's not just women runners (female runners) who are upset. Men are just as concerned, and plenty of people outside of the running community are, too, including Kamala Harris, who made a statement on Twitter in support of Cain.

2. Salazar never actually successfully explained his actions or apologized.

What Salazar does instead of apologizing is a classic narcissistic move. He states, "If I was callous or insensitive, I apologize," which puts the burden on the victim. "I'm sorry you felt that way" is quite different from "I'm sorry I hurt you." What many of us feel like he should have said is, "I'm sorry I failed you as a coach and created a toxic environment that encouraged the decline of your mental and physical health to the point where you were self-harming and unable to run to your potential," but that would probably be too much to ask.

Though Ken mentions three former NOP athletes who have also come forward to corroborate what Mary is saying, his article has only one brief quote by one of them, a single sentence. The rest of the piece is several paragraphs of back and forth, one long quote by Salazar, one paragraph defending him. And repeat.

The biggest issue I have with this kind of writing is that it discounts the victim. Instead of using her words, Ken downplays her experience by suggesting her career trailed off due to injury. No, it didn't. It trailed off because she was struggling and her coach and those around her didn't or weren't able to come to her aid. This was not her fault. Ken also didn't include the voice of other athletes who witnessed the way Salazar treated his athletes and have come forward.

The bottom line is that this is trash reporting. I could go on and on, but there's no real need. I think people see what kind of bullshit this is, and while the author eventually apologized to Kara for being an asshole on Twitter, he has a lot more to apologize for.

Labels:

health,

journalism,

Kara Goucher,

Ken Goe,

Mary Cain,

mental health,

narcissism,

Nike,

NOP,

running,

toxic environment

Sunday, November 10, 2019

A Very Old Problem Rears Its Ugly Head

There has been a lot of talk on social media about Mary Cain recently since she courageously opened up about her experiences as an athlete with Salazar and NOP. Cain joined Salazar's program in 2013 when she was just a teenager. Though she's more of a standout in terms of her performance and will always be remembered as one of the best young female track athletes ever, her backstory is like many others.

The unrelenting attention on her weight and the excessive pressure that Mary experienced is nothing new. Unfortunately, we live in a society with a mad focus on body, especially women's bodies. In the sports world, it's even more extreme, though men are not immune to negative comments by coaches and peers. In Mary's case, though, she, a young girl, was surrounded by older men associated with the program and a coach who was, according to her and several members of her team, overly critical and overly focused on her weight at the expense of her performance, her health, and her overall well-being.

What's upsetting to see in the aftermath of all of this is that some people on social media have turned the conversation into a debate about what a healthy racing weight is for her. Guess what? It's none of your fucking business. This is one problem of many and reinforces warped ideas around the female athlete's body. It's not up to anyone else to decide what's healthy, and comparing her or any young athlete to other adult runners who are leaner or heavier serves zero purpose, none. Who knows what methods people use to stay lean and fit, and with all the doping allegations being dropped, I'm sure a lot of "healthy" lean examples aren't quite. What one person weighs has no relevance to what's healthy for someone else.

This is her life, her health, and her body. Her rules now. Nobody else's. If a runner goes from running well and feeling good to a cycle of missed periods, broken bones, and poor health, there's clearly something wrong, and weight loss isn't the answer to an improvement in performance at that point.

This is her life, her health, and her body. Her rules now. Nobody else's. If a runner goes from running well and feeling good to a cycle of missed periods, broken bones, and poor health, there's clearly something wrong, and weight loss isn't the answer to an improvement in performance at that point.

Another upsetting result of Mary coming forward are the people who feel it necessary to shift the focus to another cause. This is selfish and also doesn't solve this particular issue. There are plenty of topics that deserve their time in the spotlight, but don't kick Mary to the side in order to step in her place. Take your turn at the appropriate time.

More importantly, though, his focus should have been on her overall heath, her longevity in the sport, and her training, not an arbitrary number on the scale that reflects nothing about her strength and wellness. She was a teenager. He was supposed to protect her, not burden her and then break her.

I know people mean well, but the focus on Mary right now shouldn't be on a comeback or even running, really. She already established herself as one of the greatest on the track. Why do people insist she do more? If she wants it, the opportunity is there, but her message is about SO much more. This is about the abuse of power and the enormous pressures heaped on very young athletes. This is about a broken system that has been a mess for many, many years.

What I hope people realize with this door opening is that Mary is one of many runners who had to try to survive in an unhealthy environment. When I first started telling my story, I was generally supported, especially by friends and family, but still faced people, not just men, who denied the prevalence of these kinds of issues in the running world or suggested that people like me were weak or trying to cheat in some way. It's odd to see some of these same people act as advocates now. I'm sure that's a good thing, but I can honestly say it's strange to see.

Some people insist that if it didn't happen to them, it must not be that big a problem. I and others have faced put downs and digs about mental health and eating disorders and a lot of speculation about our current state of health based on our pasts, which puts even more attention where it shouldn't be, on our bodies. It's equally upsetting that people who are healthy and lean are pushed into a corner of feeling like they have to defend themselves against accusations. This is all the result of attention being focused in all the wrong areas.

But things are changing. There will always be opportunists who jump on situations like this in order to step out on center stage, and we may never reach a point where women will have the freedom to be whatever size is comfortable and healthy for them without judgment. More and more, though, I see genuine concern and care from the masses and people coming forward asking how they can help, how they can make a difference and support a change.

Some people insist that if it didn't happen to them, it must not be that big a problem. I and others have faced put downs and digs about mental health and eating disorders and a lot of speculation about our current state of health based on our pasts, which puts even more attention where it shouldn't be, on our bodies. It's equally upsetting that people who are healthy and lean are pushed into a corner of feeling like they have to defend themselves against accusations. This is all the result of attention being focused in all the wrong areas.

But things are changing. There will always be opportunists who jump on situations like this in order to step out on center stage, and we may never reach a point where women will have the freedom to be whatever size is comfortable and healthy for them without judgment. More and more, though, I see genuine concern and care from the masses and people coming forward asking how they can help, how they can make a difference and support a change.

In a way, this has become the runners version of a #MeToo movement, and it's heartbreaking to see so many athletes come forward with stories of their own. Think of all the high school, college, and club programs that promote or promoted the same kind of unhealthy environment Mary endured. Little comments coaches make can have long-lasting effects. But it's not just the running world that's flawed. Our society is deeply in need of repair when it comes to how people view women and our bodies. It's not just women, either, but there's a relentless focus on the female body that's terribly unhealthy. Salazar and the people at Nike are products of our society, but that's no excuse. What they have done to so many athletes is awful, and the way they are handling the backlash now is inexcusable.

If the allegations are so troubling, as Nike suggested, why not simply state that an investigation will take place? What, exactly, is Nike implying with that little jab about Mary not speaking out at the time and possibly contemplating a return to her coach this year? She already stated why she stayed silent until now, and LOTS of people go back to or feel compelled to go back to abusive situations.

If the allegations are so troubling, as Nike suggested, why not simply state that an investigation will take place? What, exactly, is Nike implying with that little jab about Mary not speaking out at the time and possibly contemplating a return to her coach this year? She already stated why she stayed silent until now, and LOTS of people go back to or feel compelled to go back to abusive situations.

This has been an emotional time for may of us who have lived with the same kinds of pressures, both internal and external. But now is the perfect time to talk about change and how to make it safer for young athletes to achieve their goals while maintaining health, both emotional and physical.

In times of distress, they say to look to the helpers. In my own case, when I'm feeling down or disturbed about events in the running world, I look to people like Diane Israel, Bobby McGee, Rachael Steil, Melody Fairchild, Kara Goucher, the Roots Running Project, and my many mentors and friends for guidance. Speaking of looking to people for leadership, a friend and incredible inspiration to me and many others in the running community and in general, Tonia, wrote a spot-on blog post about the trouble with youth sports. Please take the time to read it. Things need to change.

I don't know if it's the case or people were merely speculating, but I'm glad to know others agree that the sole solution to fixing this mess is not simply hiring female coaches. That might help to an extent, but female coaches can be just as abusive. This is a systemic and even a cultural issue, and it will take a lot of effort to fix it.

What's important, in addition to providing more education around the topic, is offering every athlete access to a group of individuals not necessarily associated with their team that, in addition to the coach, would include a sports psychologist, a dietitian, some kind of advocate, and a physical therapist. This might be impossible financially for small programs, but even having someone from the outside who would be responsible for checking in on athletes periodically would be better than nothing. There just needs to be a way for young athletes to have the freedom to speak up about their experiences with their coaches in a safe environment.

As I hinted at earlier, this has stirred up a lot of emotions for me, so I'm sure I'm not addressing everything I would like and maybe addressing things in a way that's not completely coherent. Still, I felt the need to put at least some thoughts down.

Because I wish I could help more but don't exactly know how, I will just reiterate what others have been saying. I'm here if anyone needs an ear or some support. I've been through it, and I want others to know that they are not alone.

While Mary's message is about more than eating issues, I'm still going to offer a free copy of my eating disorder recovery handbook to anyone interested through the end of January 2020.

The coupon code is:

TQ39S

and the link is:

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/730896

In times of distress, they say to look to the helpers. In my own case, when I'm feeling down or disturbed about events in the running world, I look to people like Diane Israel, Bobby McGee, Rachael Steil, Melody Fairchild, Kara Goucher, the Roots Running Project, and my many mentors and friends for guidance. Speaking of looking to people for leadership, a friend and incredible inspiration to me and many others in the running community and in general, Tonia, wrote a spot-on blog post about the trouble with youth sports. Please take the time to read it. Things need to change.

I don't know if it's the case or people were merely speculating, but I'm glad to know others agree that the sole solution to fixing this mess is not simply hiring female coaches. That might help to an extent, but female coaches can be just as abusive. This is a systemic and even a cultural issue, and it will take a lot of effort to fix it.

What's important, in addition to providing more education around the topic, is offering every athlete access to a group of individuals not necessarily associated with their team that, in addition to the coach, would include a sports psychologist, a dietitian, some kind of advocate, and a physical therapist. This might be impossible financially for small programs, but even having someone from the outside who would be responsible for checking in on athletes periodically would be better than nothing. There just needs to be a way for young athletes to have the freedom to speak up about their experiences with their coaches in a safe environment.

As I hinted at earlier, this has stirred up a lot of emotions for me, so I'm sure I'm not addressing everything I would like and maybe addressing things in a way that's not completely coherent. Still, I felt the need to put at least some thoughts down.

Because I wish I could help more but don't exactly know how, I will just reiterate what others have been saying. I'm here if anyone needs an ear or some support. I've been through it, and I want others to know that they are not alone.

While Mary's message is about more than eating issues, I'm still going to offer a free copy of my eating disorder recovery handbook to anyone interested through the end of January 2020.

The coupon code is:

TQ39S

and the link is:

https://www.smashwords.com/books/view/730896

Labels:

abuse,

coach,

coaches,

Fuck NOP,

fuck Salazar,

Mary Cain,

pressures,

running,

youth running

Saturday, November 2, 2019

Too Good To Be True

I ran a 5k today. It was so cold when I went to sign up for the race that I started shivering despite being in a long-sleeved T-shirt, two layers of running pants, a thick running jacket, a regular jacket over that, and all the accessories including gloves, hat, and a neck warmer. I am not a cold weather person, at all.

It wasn't necessary to wear every layer I warmed up with, so I dropped a few at the car before the start of the race.

Almost right off the bat, I had a major issue. My hip/upper hamstring popped or snapped, as if often does, but this time it was so bad that it threw me off balance. I ended up looking like an idiot and did the whole arms flailing move to prevent a fall, and, needless to say, my pace was a little off after that. Fortunately, it didn't hurt too badly and is only a little bit sore now. I'm sure I will have to watch it closely, though.

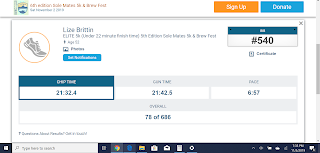

The race was a lot larger than I thought it would be, especially since it was split into two waves, the elites going 30 minutes before the rest of us joggers. Most everyone is friendly at these types of events, but today I encountered two or three guys who blatantly cut me off without even a nod of acknowledgment. Since I was already struggling with manoeuvring over some of the icy patches, so much so that I actually made things more difficult on myself and took a few steps here and there on the snow to the side of the path, the whole race felt very slow. With all the stagger steps and awkward ballet leaps I was doing on the course, I was super surprised and briefly allowed myself to be hopeful and excited when I saw the results below.

It wasn't necessary to wear every layer I warmed up with, so I dropped a few at the car before the start of the race.

Almost right off the bat, I had a major issue. My hip/upper hamstring popped or snapped, as if often does, but this time it was so bad that it threw me off balance. I ended up looking like an idiot and did the whole arms flailing move to prevent a fall, and, needless to say, my pace was a little off after that. Fortunately, it didn't hurt too badly and is only a little bit sore now. I'm sure I will have to watch it closely, though.

The race was a lot larger than I thought it would be, especially since it was split into two waves, the elites going 30 minutes before the rest of us joggers. Most everyone is friendly at these types of events, but today I encountered two or three guys who blatantly cut me off without even a nod of acknowledgment. Since I was already struggling with manoeuvring over some of the icy patches, so much so that I actually made things more difficult on myself and took a few steps here and there on the snow to the side of the path, the whole race felt very slow. With all the stagger steps and awkward ballet leaps I was doing on the course, I was super surprised and briefly allowed myself to be hopeful and excited when I saw the results below.

Since I messed up starting my watch and didn't actually press the button until several minutes into the race, I had no idea what my time was. After giving the events of the morning more thought, I started to suspect the course was short. It turns out it's not, and my result was updated a few hours later with my real time. Who knows how this kind of error happens, but my actual time was a lot slower.

It's funny because I ran almost that exact time on a course last year and was really happy with it, but I felt like I had a lot of room for improvement this time. As a result, I'm not very pleased with my time or my effort. Then again, it really wasn't my day today, and yet I still managed to win my age group. That was a surprise.

Maybe tomorrow my time will be updated to 25:00, and then I will be even more disappointed.

I'm already dying for spring. It's going to be a long winter.